If you’ve ever watched a South American clásico and thought “this is pure chaos,” you’re half right. It *looks* chaotic, but there’s a lot of structure under all that intensity. Let’s break down a detailed tactical analysis of the latest clásicos in a way that feels like sitting in a bar with a whiteboard instead of a TV pundit studio.

—

Historical context: why South American clásicos are tactically different

When we talk about análisis táctico clásicos del fútbol sudamericano, we’re not just talking about formations or pressing schemes. These matches are born from decades of rivalry, politics, social class clashes and club identity. Boca–River, Peñarol–Nacional, Flamengo–Fluminense, Colo-Colo–La U, Racing–Independiente… these games didn’t become “clásicos” because of marketing. They’re closer to local derbies with national consequences.

Historically, you can trace a shift from “romantic chaos” to “organized aggression.” In the 70s and 80s, many clásicos were decided more by physicality and individual talent than by collective pressing triggers. In the 90s and early 2000s, defensive solidity and low blocks became more visible, especially in Libertadores ties. The recent generation (roughly post-2015) shows something different: European-influenced structures adapted to South American reality—tighter schedules, worse pitches, travel, and squads with constant player turnover.

In short: same emotional temperature, much more sophisticated game plans.

—

Basic tactical principles that repeat in almost every clásico

Even if coaches change and line-ups rotate, a few core ideas keep coming back in the mejores clásicos del fútbol sudamericano resumen y análisis. If you start looking for these patterns instead of just watching the ball, clásicos become 10 times more interesting.

Long story short, three principles dominate:

– Control of the *second ball*

– Asymmetry in wide areas

– Manipulation of emotion (yes, that’s a tactical tool)

Let’s unpack them so you can actually spot them next time you watch.

—

Second balls: the hidden “possession” battle

Forget sterile possession stats for a second. In recent clásicos, especially in Argentina, Uruguay and some Brazilian derbies, the real battle often happens after the first duel: the second ball. You’ll see it in practically every high punt from the keeper, long diagonal from a centre-back, or contested aerial duel near the halfway line.

Coaches structure their teams to win the *space around the duel*, not just the duel itself. For example:

– The “duel zone” is overloaded with 4–5 players ready to react to the first header or loose touch.

– The far-side winger often tucks infield to form a temporary square with two midfielders and one full-back.

– The No. 9 positions not just to win the header, but to block the opponent’s pivot from stepping into the second ball.

What looks like chaos is often a pre-planned “battle box” around the ball. If you pause the screen at the moment of a long ball, you’ll notice both teams have compact 20–25 meter blocks instead of neat 4-3-3 lines.

Non-standard tweak you can actually use as a coach:

Assign one player the explicit role of “second-ball captain.” Their job is not to chase the ball blindly, but to:

– Orient nearby teammates with constant communication (“step / drop / left / right”)

– Read where the clearance *should* go, not where it currently is

– Be the first to *secure* the ball with the correct body orientation (open hips, half-turn stance)

This role is rarely named out loud in team talks, but formalizing it can immediately tidy your team’s shape in high-intensity games.

—

Asymmetry: attacking one flank, defending the other

Another recurring pattern: South American clásicos love asymmetrical shapes. Instead of both full-backs bombing forward in perfect Pep-style symmetry, you see:

– One full-back becomes a third centre-back in build-up.

– The opposite full-back pushes high like a winger.

– The near-side winger sometimes tucks inside to create a box midfield (2+2) or even a diamond.

From the stands, it looks improvisational. On the tactical cam, it’s deliberate: coaches use asymmetry to attack the weaker defensive side of a rival while securing rest-defense with three or even four players behind the ball.

If you’re building your own model, steal this structure:

Right-back stays, left-back goes high, left winger drifts inside to the half-space, while the right winger stays touchline wide to stretch horizontally. This gives you:

– 3+2 rest-defense (three defenders + two midfielders)

– Occupied half-space for combinations

– Clear “escape route” to the far side if the overloaded wing gets crowded

—

Emotion as a tactical variable, not background noise

Here’s where South American clásicos differ most from many European derbies: the emotional wave isn’t a side effect; it’s part of the plan. Coaches design game phases around it.

You’ll often see three emotional “blocks” in game plans:

– First 15–20 minutes: Either ultra-high pressing to harness the crowd’s energy or extreme control to “cool” the stadium.

– Post-goal periods: Pre-defined triggers—after scoring, some teams instantly drop into mid-block for 5–7 minutes. After conceding, they push full-backs higher than usual to signal aggression.

– Last 15 minutes: Substitutions not just for freshness, but to introduce players who can draw fouls, slow tempo or stretch transitions.

A clever, underused idea: assign one of your quieter players as the “emotional anchor.” Their job is to *visibly* slow things down—extra touches, calm gestures, deliberate scanning—exactly when the rest of the team is speeding up irrationally. This is tactical time control, not just “experience.”

—

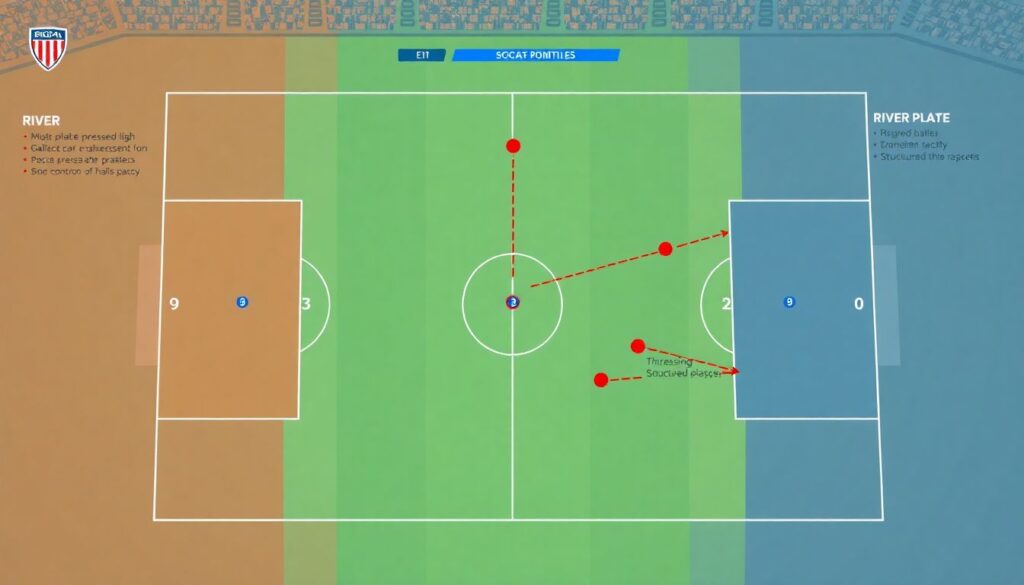

Superclásico River–Boca: what “in-depth analysis” really looks like

When people mention análisis táctico en profundidad superclásico river boca, it often gets reduced to “Gallardo pressed high” or “Boca was more direct.” That’s surface-level. The recent editions of this fixture show three recurring tactical battles:

1. Who controls the half-spaces?

River, especially under Gallardo, tried to dominate the pockets between full-back and centre-back. Boca often responded with narrow wingers helping full-backs, accepting 2v1s wide to protect central lanes.

2. Where does Boca’s first build-up line actually start?

In some matches, Boca dropped their No. 6 between centre-backs, forming a temporary back three to bait River’s first pressing line. Other times they used long diagonal balls to bypass River’s press altogether and play for the aforementioned second balls.

3. River’s “positional rotations” vs Boca’s “positional anchors”

River rotated interiors with wingers and even full-backs, while Boca usually kept clearer reference points: one striker pinning the centre-backs, one winger attacking depth, one midfielder screening the back line.

Unconventional idea if you coach a “River-style” team:

Instead of rotating *all* your attacking players, choose one “anchor” (usually the No. 9) who never leaves the central lane. This gives your rotating players a fixed reference point and simplifies third-man combinations in high-traffic zones.

—

Other clásicos: Flamengo–Fluminense, Peñarol–Nacional, and beyond

The mejores clásicos del fútbol sudamericano resumen y análisis in recent years reveal some consistent themes across different countries, but with local flavors.

– Flamengo–Fluminense (Fla–Flu) often becomes a battle of pressing height. Flamengo’s squads usually have more talent between the lines, so Flu frequently sets traps wide, inviting Flamengo’s full-backs to receive under pressure and then countering behind them.

– Peñarol–Nacional tend to be compact and transitional. The pitches and match context (many in tight league races or Libertadores qualifiers) favor tight lines, verticality and heavy reliance on set-pieces.

– Colo-Colo vs Universidad de Chile often feature aggressive wing play, with both teams using wide overloads and underlaps to break man-oriented or mixed marking systems.

If you want to scout these matches tactically, don’t start with formations. Start with:

– How high they press on goal kicks

– Who defends the half-spaces out of possession

– Whether the pivot stays or joins the press

You’ll understand the match plan much faster than reading a line-up graphic.

—

Basic principles you can apply when analyzing any clásico

To make your own análisis actually useful (not just “they were more intense”), turn every clásico into a mini case study. Here’s a simple framework.

When the opponent builds from the back, ask:

– Who forms the first line: 2, 3 or even 4 players?

– Where does the pivot stand: between centre-backs, alongside, or higher?

– What zone do they *avoid* (rarely pass into)? That’s usually where they feel least secure.

When *your* team has the ball under pressure, check:

– Are you losing the ball more often in wide zones or central zones?

– Does your 9 help in build-up or stay high to pin the line?

– How many players are actually behind the ball when you lose it?

That last detail (rest-defense numbers) is where many clásicos are decided: one rushed attack, poor structure behind the ball, and your rival scores from a 4v3 counter.

—

Unconventional tactical solutions for high-emotion derbies

Let’s move from observation to invention. If you coach or analyze, here are some out-of-the-box tweaks that surprisingly fit South American clásicos:

– “Fake weakness” wing

In your pre-match pattern, repeatedly show vulnerability on one flank—slightly wider full-back, winger not tracking all the way. The rival will naturally funnel attacks there. But your real plan is to crowd that side with a defensive midfielder sliding over, a tucked-in winger from the opposite side, and your nearest centre-back stepping aggressively. You’re baiting them into your pressing trap.

– Rotating set-piece zones

Instead of always attacking the same zones on corners (first post, penalty spot, second post), assign three preset patterns and rotate them *every 10–15 minutes*, not every corner. The opponent adjusts to something that has already changed, buying you two or three dangerous unchallenged runs.

– Pre-planned “calm phase” after substitutions

Most coaches throw on substitutes and hope they adapt. In clásicos, plan a 3–4 minute “calm phase” where the team is instructed to: keep the ball, avoid forced vertical passes, and re-establish structure so subs know exactly where to stand and what lanes to cover. You sacrifice a bit of chaos to gain massive organization.

—

Why video and data matter (even at amateur level)

A lot of people still think serious match analysis is only for pro clubs or fancy estudios tácticos partidos clásicos sudamericanos pdf. But you can replicate 70% of that insight with basic tools:

– One wide-angle camera behind the goal or high in the stands

– Simple tagging: mark timestamps for goal kicks, throw-ins, set-pieces, transitions

– A shared folder where staff and players can replay key phases at x1.5 speed

You’re not trying to build a massive report. You want 8–10 clear clips that show repeated patterns: for or against you. If those clips line up with what you *thought* you saw live, great. If not, your eye test needs adjusting.

—

Common misconceptions about South American clásicos

Let’s clear out a few myths that keep popping up in fan debates and lazy match reports.

1. “Clásicos are pure heart, little tactic.”

False. The emotional layer is thick, but recent derbies show clear game plans, training-ground patterns and adapted European concepts. The difference is that execution sometimes breaks under pressure.

2. “It’s all about the individual talent.”

Individual brilliance matters, especially for breaking low blocks. But without structure—distance between lines, rest-defense, clear pressing heights—talent gets isolated. Many recent clásicos were decided by collective mechanisms like back-post overloads or coordinated counter-pressing, not just solo runs.

3. “Formations tell you everything.”

The 4-2-3-1 vs 4-3-3 graphic is almost meaningless on its own. What decides the match is *behaviour*: who jumps to press, who covers, who protects the pivot, and what happens in transitions. Formations are a starting point, not a conclusion.

4. “You need pro-level tools to analyze properly.”

Not really. Even without a suscripción web análisis táctico fútbol sudamericano profesional, you can get far with a notebook, a basic camera and the discipline to rewatch key phases. The difficult part isn’t the software—it’s knowing what to look for.

—

How to structure your own clásico analysis (and improve quickly)

If you want your work to approach the level of formal estudios tácticos partidos clásicos sudamericanos pdf, keep your process simple and repeatable:

– Phase 1 – Live notes:

– Mark pressing height in first 10 minutes.

– Note how each team builds from goal kicks.

– Identify which side (left or right) becomes the “main highway” for attacks.

– Phase 2 – First rewatch (no pause):

– Focus only on ball losses and transitions for each team.

– Ask: who is behind the ball? who reacts first? who stays passive?

– Phase 3 – Second rewatch (with pauses):

– Capture 3–4 clips of build-up, 3–4 of pressing, 3–4 of set-pieces.

– Add 1–2 clips of emotional swings (right after goals or big fouls) to see how the team shape changes.

Do this for 5–6 clásicos in a row and your eye for structure will improve far more than by just reading analysis threads.

—

Closing thoughts: turning passion into an edge

The magic of South American clásicos is that they compress everything—history, identity, pressure and talent—into 90 frantic minutes. Underneath that, there’s a clear tactical spine: second-ball dominance, asymmetry, emotional management, rest-defense, and tailored pressing plans.

If you’re coaching, start with one or two ideas from above—maybe defining a “second-ball captain” or designing a fake-weakness wing trap—and test them in your next high-stakes match. If you’re a fan or analyst, go beyond the goals and cards: watch the distances between lines, the behaviour after ball losses, and how teams ride or resist the emotional waves.

That’s where the real clásico lives.